Kimia Afshar Mehrabi

Independent Study

INDEPENDENT STUDY

Tackling Toronto's gun violence needs improved investments in education, housing, and community

At first, a birthday party at Forty2 Supperclub in Toronto seemed like the perfect night. Club goers were dressed in all their fancy attire, and the warmth of the summer remained despite the September breeze.

However, the night took a dark turn for Kiesingar Gunn, 26. The father of four was hit by a stray bullet as an altercation occurred outside of the nightclub near Liberty Street and Mowat Avenue in 2016.

Despite a $50, 000 reward, composite sketch, and surveillance video of the shooter’s vehicle, Gunn’s homicide remains unsolved. He was the city’s 49th homicide incident that year, although police do not believe he was the intended target of the shooting.

After her son’s death, Evelyn Fox began searching for online support for families of loved ones who were victims of homicide in Toronto. She found little she considered helpful, so Fox created a community organization called Communities for Zero Violence.

“It was very difficult to find support for all of us, because they literally did not exist,” Fox said.

Evelyn Fox and her son, Kiesingar Gunn, 26, who was killed by a stray bullet outside Forty2 Supperclub in Liberty Village on Sept. 11, 2016. Photo credit: Courtesy/Evelyn Fox

She said her organization tries to connect with families as soon as a homicide occurs.

“When your child is killed, you’re in shock, your brain is trying to process what happened,” Fox said.

She said gun violence continues to impact communities of young people across Toronto.

“We have a lot of children that are traumatized, they’re living with trauma,” Fox said. “They just want to survive.”

Over the past several years, gun violence in the city has become a more prominent issue among adolescents and young adults. One case involves Grade 12 student Jahiem Robinson, 18, who was shot and killed by a 14-year-old student at David and Mary Thomson Collegiate Institute in Scarborough, on Feb. 14, 2022.

The shooter, who cannot be named under the Youth Criminal Justice Act, was arrested and charged with first-degree murder and attempted murder.

Jahiem Robinson, 18, was the victim of a fatal shooting at David and Mary Thomson Collegiate Institute in Scarborough on Feb. 14, 2022. Photo credit: Courtesy/Toronto Police Service

In a letter written to the community, school principal Aatif Choudhry said Robinson was a constant source of support to his friends at school.

“He was dependable, sympathetic, and always available to talk to those who needed him,” Choudhry said.

After the incident, Liberal MPP for Scarborough-Guildwood Mitzie Hunter wrote a letter to Ontario’s Minister of Health Christine Elliot, urging the province to pass Bill 60. Otherwise known as the Safe and Healthy Communities Act, the bill would have created community-based intervention programs and deemed gun violence a public health emergency.

It stalled at the Standing Committee on Justice Policy and then died on the order table as the provincial election was called for June.

What occurred at David and Mary Thomson Collegiate is not an uncommon tale in many of Toronto’s neighbourhoods. Over the past several years, gun violence in the city has become a more prominent issue among adolescents and young adults.

Toronto Deputy Chief of Police Myron Demkiw revealed some alarming statistics regarding gun violence at a news conference days after Robinson’s murder. He said the average age of those linked to gun violence in Toronto between 2015 and 2020 was 25 years of age but dropped to 20 in 2021.

“There is no rational explanation for why a 13-, 14-, or 15-year-old child should have access to illegal firearms, let alone feel compelled to use them,” Demkiw said.

A Jan. 22 shooting in North York involving three teens highlighted the increasing connection between youth and gun violence.

Three Oshawa teens, two aged 16 and the third 15 were arrested in connection with the death of another teenager, Malachi Elijah Bainbridge, 19, who was shot and killed outside a North York McDonald’s near Keele Street and Ingram Drive shortly before 1 a.m.

One boy, 16, is now facing a single count of first-degree murder.

Fox said the issue boils down to the support children receive at school, and more importantly, at home.

“They’re labelled problem children, instead of having a child youth worker,” she said. “They’re suspended, expelled back into the street, where they already feel anger and upset because they have no control over their life outside of the school system.”

Just a month before Robinson’s murder, a 13-year-old boy shocked the city when he shot and killed a 15-year-old boy in an underground parking garage in Toronto’s east end. Jordon Carter was killed around 11:30 p.m. at a garage near Pape and Gamble Avenues.

Jordon Carter, 15, was shot and killed by a 13-year-old boy in an underground parking garage near Pape and Gamble Avenues on Jan.19, 2022. Photo credit: Courtesy/Toronto Police Service

The 13-year-old youth was charged with second-degree murder as well as several firearm-related charges.

Staff Superintendent Lauren Pogue, with the service Detective Operations unit, said at a news conference following Carter’s murder there has been a disturbing rise in gun violence over the last several months.

“Gun violence is an issue with many layers of complexity and trauma,” Pogue said.

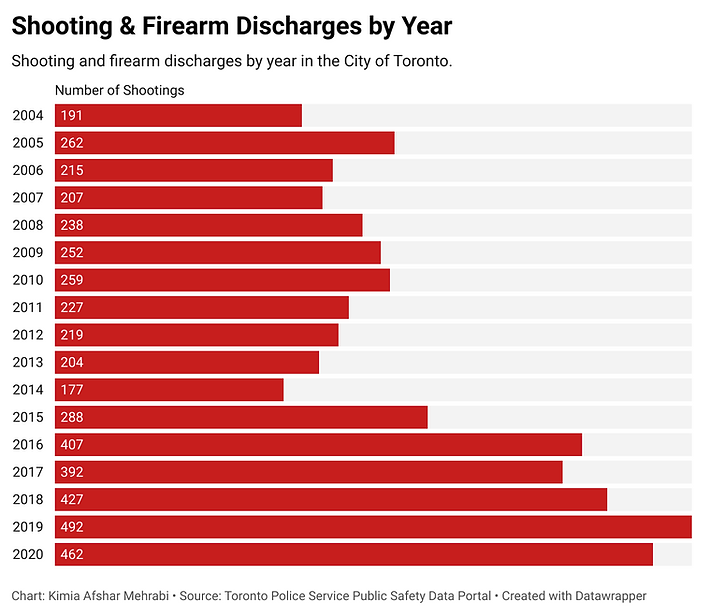

The Toronto Police Public Safety Data Portal shows gun violence has been steadily increasing in the city since 2004.

From 2015 to 2020, the average number of shootings per year had climbed to 436 incidents. This figure is nearly double the annual average number of shootings before 2015.

In 2022 alone, 27 of the 40 homicides so far have been related to shootings. Out of all the homicides this year, 68 per cent have been firearm related.

There were 85 homicides in Toronto in 2021, and of those, 46 — or 54.1 per cent — were because of a shooting.

It is no secret that the extent and presence of gun violence differs dramatically across neighbourhoods in Toronto.

A Toronto Police dataset showed that Toronto’s Glenfield-Jane Heights neighbourhood saw more firearm-related injuries than any other neighbourhood between 2017 and 2021, with 51 injuries.

Other neighbourhoods which experienced high levels of firearm-related injuries in the past five years include Mount Olive-Silverstone-Jamestown (32), Downsview-Roding-CFB (29), Waterfront Communities-The Island (27), Black Creek (24), and West Humber-Clairville (22).

Additional neighbourhoods with high firearm-related injuries include Oakwood Village (21), Woburn (21), and York University Heights (21).

_p.png)

Former Humber College student Nosa Aigbogun, 25, has lived in the Glenfield-Jane Heights neighbourhood for more than 10 years. While he has not been involved in gun violence, he knows several people in his neighbourhood who have been involved.

“Everybody here has at least heard of one person who’s been involved in gun violence,” he said.

Aigbogun said he remembers a time when he had a close call with a shooting near his own house.

“One time, late at night, I was walking back from a friend’s house in the area to mine,” he said. “I woke up to my messages being flooded with worried texts from friends about my safety.”

Aigbogun said a shooting occurred just down his street at about the time that he left his friend’s house.

“It is only a 10-minute walk away and in the time I had left and gotten home, a shooting on my walking path had happened and my friends were concerned,” he said. “It is a harsh reminder of how close these events are to home, and a sad reality of how easily we can lose people.”

Aigbogun said he would hear about a shooting incident in his neighbourhood almost every few weeks.

“After seeing reoccurring shootings in the area, I can say I have a bit of desensitization when it comes to the news,” he said.

Aigbogun said he thinks gun violence in Glenfield-Jane Heights can be managed through programs for the community.

“Obviously gun violence is a very extensive and deep-rooted issue,” he said. “But things such as programs for youth to help them in education combined with support for lower-income families can really help.”

Founder of the Zero Gun Violence Movement in Toronto Louis March visits neighbourhoods such as Glenfield-Jane Heights regularly.

Founder of the Zero Gun Violence Movement Louis March at a Black Lives Matter protest in Regent Park in 2020. Photo credit: Courtesy/Louis March

March said if socio-economic conditions are not balanced throughout the city, gun violence will continue.

“There’s a difference between living in Rosedale and living in Rexdale,” March said. “Your livelihood, your life expectancy, and the quality of your life is dependent on your postal code.”

March’s movement collaborates with more than 40 community programs and agencies across Toronto to address the socio-economic conditions that worsen gun violence. He said government-funded programs are failing certain communities in Toronto.

“How do we get the government to change the way they look at gun violence and the way they respond to it through policies?” he said. “Are they really addressing the issue of gun violence? Or are they just band-aids?”

March said gun violence disproportionately affects communities like Glenfield-Jane Heights and Scarborough.

“If you go to certain communities like Rosedale, when the sun settles, everybody comes out to have fun,” he said. “If you go to Rexdale when the sun sets, everybody runs inside, the playground is empty, there is no laughter.”

Scarborough continues to be one of the neighbourhoods most affected by gun violence in Toronto. Just recently, a 27-year-old man was fatally shot by Toronto police outside an elementary school in Scarborough.

Officers were called to the area near Lawrence Avenue East and Port Union Road after receiving reports of a man carrying a gun near William G. Davis Junior Public School.

Two officers shot at the man, and he was later pronounced dead at the scene. Following the shooting, officers discovered the man was carrying a pellet gun.

March said he has talked to hundreds of young people that live in neighbourhoods with high rates of gun violence throughout the course of his career.

“If I go to a group in Lawrence Heights, and I have 20 young people there, and I ask them how many of you here have lost somebody to gun violence? They will all put up their hands,” he said.

March said he has had many heart-wrenching conversations with families who have lost loved ones to gun violence.

“I had a conversation with one mother who lost her two sons to gun violence, I don’t know how she does it, but she does,” he said. “After my presentation at Ryerson University, she came up to me when I was finished, and said ‘you didn’t mention the word love once.’”

March said he wasn’t there to talk about love, he was there to talk about gun violence.

“Her response to me was, 'if I can lose my two sons to gun violence, and I can speak about love, I don’t see why you can’t, because the solution to gun violence has to be about love,'” he said.

March said the Zero Gun Violence Movement stresses that increased police presence will not solve the issue of gun violence in the city.

The organization’s website states, “gun violence in Toronto is a manifestation of the poor policy decisions that our policymakers have continued to make despite the overwhelming evidence that there is a glaring absence of equality of opportunity for the vast majority of Toronto’s African-Canadians.”

March said young people in low-income neighbourhoods look to gun violence to solve many of their problems.

“Housing, nutrition, drug activity, all these types of things are challenges as you grow up in these communities,” he said. “Drug dealing then becomes a viable option to make money and survive.”

The provincial government has made plans to try to tackle gun violence in Ontario’s most populated city.

Ontario announced in April that over the next three years, it will give Toronto Police Service $87 million to fight gun and gang violence.

Of that, $14.7 million will be specifically directed to establishing a “gun, gangs and violence strategy.”

Solicitor General Sylvia Jones said the provincial investment will help build a safer Toronto.

“This significant investment will help the Toronto Police Service and their community partners protect neighbourhoods, fight crime and hold offenders accountable,” Jones said.

Toronto Police Chief James Ramer said the initiative will allow police to deploy to the areas that require the most resources.

“This significant funding will allow us to enhance community safety resources in Toronto, including helping to address gun and gang violence and by expanding the Neighbourhood Officer Program, both of which are priorities of our communities,” Ramer said.

However, March said gun violence cannot be solved by a one-time investment or program.

“We have abdicated the responsibility to police and politicians, what has that gotten us?” he said. “The public has a significant role because as long as the public turns a blind eye to it, the gun violence will continue.”

The municipal government has also had its fair share of attempting to mitigate the city’s gun violence.

City Council revealed the SafeTO strategy in 2021. The initiative promises to develop a gun violence reduction plan and invest $12 million during its first year. Photo credit: Courtesy/City of Toronto

Toronto City Council adopted SafeTO on July 14, 2021, a 10-year plan with 26 priority actions across seven strategic goals: reduce vulnerability, reduce violence, advance truth and reconciliation, promote healing and justice, invest in people, invest in neighbourhoods and drive collaboration and accountability.

The plan involves developing a comprehensive multi-sector gun violence reduction plan.

City council said it was preparing to spend up to $12 million during the first year of the plan.

Toronto plans to expand the program to help individuals who have been impacted by violence directly, including shootings.

More city staff will be hired to be quickly deployed to communities impacted by gun violence.

March said the solution to gun violence is not as difficult as people make it out to be.

“What is lacking is political will, political courage, and political direction,” he said. “You can’t deal with gun violence if you don’t deal with education, housing, community investments, and a police force that protects everybody.”

March said the neighbourhood youths live in can dramatically impact their socio-economic conditions, and ultimately their relationship with gun violence.

He spoke to the Toronto Board of Health at City Hall in 2019 where he stressed the importance of sending resources to specific communities.

“We already have zero-gun violence in the city of Toronto,” March said. “But it only exists in certain communities for certain people.”

He said between 2014 and 2019, Toronto had more than 2,000 shootings and more than 3,000 victims of gun violence. March said gun violence does not just affect the people physically hurt by it, but it pours across several families and communities.

“When we talk about trauma, for every one of those shootings, for every one of those victims, for every one of those homicides, you multiply it by 10, and you’ll get the real information on what is going on,” he said.

Fox said the loss of her son has been a severe roller coaster of emotion and anger for her.

“My household right now is going through waves of anger and sadness,” she said. “It’s two of us that have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Fox said she finds it difficult to celebrate days like his birthday given his absence.

“I’m nowhere near the same person that I used to be,” she said. “My son always was like, ‘how come you don’t smile anymore?’ I’m like, what am I smiling about?”

Fox said she doesn’t know if she will ever get to a place where she feels joy all the time.

“It’s really difficult to know that the person who killed my son is living his life with no accountability,” she said. “But my family has been destroyed.”